What do the following public statues have in common?

Fenway Park has a statue of Ted Williams, the TD Garden has a statue of Bruins star Bobby Orr, and Boston College has a statue of Heisman trophy winner Doug Flutie.

Answer: They are all statues of white athletes in one city: Boston, Massachusetts.

When President Barack Obama recently bestowed The Presidential Medal of Freedom on black NBA legend Bill Russell, he decided lend the prestige of the Presidency to this trivial apparent discrepancy.

"I hope that one day, in the streets of Boston, children will look up at a statue built not only to Bill Russell the player, but Bill Russell the man." [Give him honor, Obama says, By Michael Levenson, Boston Globe, February 16, 2011]

Suddenly, the city of Boston is in a tizzy to erect a statue of Bill Russell.

Yes, the Boston political class is in the midst of another "Do The Right Thing" moment. In Spike Lee's film, a group of black men enter a white-owned pizzeria, and demand to know "Why aren't there any pictures of black folks on the wall"?

The trend is apparently contagious. Across the Charles River, Harvard University has established a "Minority Portrait Project" to create portraits of minority faculty and alumni, so that they may hang beside portraits of the Anglos who once exclusively comprised its students and faculty.

The story on Bill Russell goes something like this: Bill Russell was a great athlete who continually endured racial slights and slurs while playing for the Boston Celtics during the 1960s. And this (we are now told) is a wrong that Boston must now right by dedicating a statue of Bill Russell.

Granted, it's not as if there are no memorials to blacks in downtown Boston. There is a statue of the poet Phyllis Wheatley on Commonwealth Avenue, a large high-relief bronze memorial to the all-black 54th Regiment on the Boston Common, the African Meeting House on Beacon Hill, a "Black Heritage Trail". You get the idea.

However, in my opinion the most interesting statue in Boston is the one in Park Square that commemorates the Emancipation Proclamation. The statue features Abraham Lincoln extending his hand over a crouched Negro slave, who is shirtless, shackled, and has a zombie-like gaze.

However, in my opinion the most interesting statue in Boston is the one in Park Square that commemorates the Emancipation Proclamation. The statue features Abraham Lincoln extending his hand over a crouched Negro slave, who is shirtless, shackled, and has a zombie-like gaze.

I'm always surprised that no one ever complains about the benighted depiction of the slave here. But to me, the statue actually explains more about the mentality of Boston elites than it does about Lincoln or slavery.

The politics of racial guilt have long been a part of the elite and academic culture of Massachusetts. And they never enjoy racial hand wringing more than when it's done at the expense of other whites—those that oppose mass immigration, forced busing, and who like to root for local sports teams, something many elites consider pedestrian.

This brings us to the subject of Bill Russell.

Bill Russell was the centerpiece of the greatest dynasty in sports history. The Russell-led Boston Celtics won eleven NBA titles in thirteen seasons (1957-1969). What was their secret? They excelled at what former NBA star Darryl Dawkins (who is black) calls "white basketball."

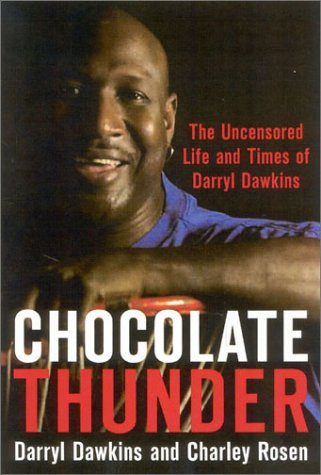

In his book, Chocolate Thunder: The Uncensored Life and Time of Darryl Dawkins

In his book, Chocolate Thunder: The Uncensored Life and Time of Darryl Dawkins Dawkins describes the difference between "white basketball" and "black basketball." According to Dawkins, "white culture places more of a premium on winning" while black culture indulges in too much "self indulgent preening and chest beating."

"White guys are more willing to do something when somebody else has the ball—setting picks, boxing out, cutting just to clear a space for a teammate, making the pass that leads to an assist. In white basketball, there's more of a sense of discipline, of running set plays and only taking wide open shots."

For decades, the Boston Celtics were the ultimate white basketball team. And few played white basketball better than Bill Russell.

As a center, Russell excelled at rebounding, passing, setting picks, and most of all, blocking shots. His emphasis on defense virtually revolutionized the game.

Bill Russell, of course, never could have excelled at black basketball even if he tried. A mediocre shooter, he never averaged more than 19 points per game in a season. But that didn't matter to Russell because, as one teammate put it, he had a "neurotic need to win."

But however much Bill Russell may have been a great team player on the court, he was an unabashed prima donna off of it. He often refused to practice, preferring to sit in the stands and drink tea as his teammates hustled through drills. He wore fancy suits, draped himself in a grand, flowing black cape, and drove a Lamborghini.

Most infamously, Bill Russell refused to sign autographs for the fans, even for children. He once described autograph seeking kids as "little monsters out hunting scalps".

The Boston sports media made much of Russell's refusal to sign autographs, and it led to considerable tension between himself and the fans.

In 1964, Bill Russell told the Saturday Evening Post

"What I'm resentful of, you know, is when they say that you owe the public this and you owe the public that. You owe the public the same thing it owes you. Nothing! . . . I refuse to smile and be nice to the kiddies." [I Owe The Public Nothing, January 18, 1964]

Let's face it: that "public" was largely made up of white people. And their support for the Celtics made Bill Russell the league's highest paid player, and one of the wealthiest black men in the country.

In an interview the previous year with Sports Illustrated, Bill Russell was even blunter: "I dislike most white people because they are people. As opposed to dislike, I like most black people because they are black." [We Are Grown Men Playing A Child's Game, by Gilbert Rogin, Sports Illustrated, Nov 18, 1963]

In the wake of his controversial statements, some thugs broke into Russell's home, sprayed racist graffiti on the walls, and even defecated into his bed.

Bill Russell blamed white racism for the crime, and who can argue? Still, when you express such hostility for the fans, you shouldn't be surprised when some of them reciprocate. No other black Celtics had their homes vandalized.

Incidentally, despite Bill Russell's professed disdain for whites, he has always preferred to live in white neighborhoods, and to date white women. He even married two white women, including Miss USA 1968.

Despite such controversies, the Celtics made Bill Russell the first African-American to coach a major league professional sports team in 1966.

Russell initially planned to retire to Liberia. He had been involved in the Black Power Movement and even named his daughter after Kenyan dictator Jomo Kenyatta, a leader of the Mau Mau rebellion against British rule. But he abandoned the idea after he lost a fortune investing in a Liberian rubber plant.

In 1972, the Celtics wanted to retire Russell's number during a game he was covering as a television commentator. But Russell insisted that the Celtics do so before the game in an empty Boston Garden so that no fans could attend.

In 1975, when the NBA Hall of Fame made Bill Russell its first black member, he again refused to attend the ceremony. Russell called the Hall of Fame "racist" and then later complained that his uniform had been displayed on a white mannequin.

In his book, Second Wind: Memoirs Of An Opinionated Man,

In his book, Second Wind: Memoirs Of An Opinionated Man, Russell says this about Boston:

"To me, Boston itself was a flea market of racism . . . If Paul Revere were riding today, it would be for racism: 'The niggers are coming! The niggers are coming!' He'd yell as he galloped through town to warn neighborhoods of busing and black homeowners." [Links added].

Unfortunately, Bill Russell's many aspersions have helped to exaggerate Boston's reputation as a racist city, and the Celtics reputation as a racist team.

The truth is that while the Boston Celtics became a dynasty by playing "white basketball", they were a virtually color-blind organization. In 1950, the Celtics drafted the NBA's first black player and in 1962 they had the league's first all black starting five.

On one occasion, Bill Russell brought his grandfather into the Celtics locker room after a game, and the man broke down into tears as he witnessed the genuine camaraderie between the black and white players.

During the 1980s, the Boston Celtics formed another great white ball team led by Larry Bird.

Boston's elites often speak as if fan enthusiasm for Larry Bird's Celtics was based on the team's whiteness. They tend to overlook the fact that the Bird-led Celtics won three NBA titles in one decade.

Besides, why is it racist to cheer for Larry Bird because he is white—but perfectly fine to root for Bill Russell or Jackie Robinson because they are black?

And it's not hard for a player to be popular when he doesn't insult the fans and actually signs autographs for children.

Nevertheless, the Boston political class and the local media continually lecture the public on how Bostonians just won't root for black athletes.

So after Bird's retirement in 1992, the Celtic ownership relented and made the switch to black basketball. They spent the next two decades floundering in the NBA.

The famous "Celtic Mystique" vanished and the team did not win another NBA title until 2008—a 22-year title drought.

As for Bill Russell, he actually does sign autographs now—for a price. In recent years Russell has made millions in the sports memorabilia business.

Not once has Bill Russell ever once apologized for the way he has disparaged the city that made him rich and famous.

Does it not seem strange for a city to dedicate a statue to a man who clearly loathes it?

The obvious location for a statue of Bill Russell would be outside the TD Garden where the Celtics play. But I doubt that will happen.

Instead, in the manner of the statue of Lincoln freeing the slaves, Boston's elites will place the Bill Russell statue somewhere downtown so that no one will be able to miss it.

They will do this not because they seek to applaud Bill Russell, but to applaud themselves for recognizing him.

Around here, they consider this "Doing The Right Thing".

Matthew Richer (email him) is a writer living in Massachusetts. He is the former American Editor of Right NOW magazine.