Earlier: Townsman of a Stiller Town—In Memoriam Martin Rojas

VDARE.com Editor Peter Brimelow writes: When I learned that Martin was working on this article, I begged him to let VDARE.com publish it, but he very honorably felt obligated by his agreement with Kevin MacDonald (whose tribute to Martin is here) and it was posted on Occidental Observer (where you can leave comments) on September 15, 2021. We reproduce it here by kind permission. Originally attributed to “Christopher Martin,” we have here substituted his real name, as far as I know the only time it has occurred as a byline, because of the freedom granted him by death after it was denied him in life by the country he loved. For the pseudonyms that America's ongoing communist coup forced him to use, see note at the end of this article.

Introduction

For years, I’ve wanted to go to southern West Virginia and do original reporting on what’s alternatively called “the white death” and “the opioid crisis.” It is the greatest social malady of our time, and people who read this publication should care about its resolution more than anyone else. After more than a year of false starts, I secured private funding to go there, specifically, to McDowell County, the nation’s poorest and least healthy county, just east of Kentucky and abutting Virginia to the south in what used to be “coal country.” By way of disclaimer, I told everyone the truth: That this project was taken on as a freelance project and I wasn’t sure where it would be published. I did not advertise my more controversial views. For the sake of everyone’s privacy, each person I spoke to is described and quoted anonymously.

Finally, this essay is not the end result of a research project. I leave the task of documenting the sociological and economic origins of this crisis to historians and authors capable of obtaining grants and book deals. What I set out to do here was speak to actual residents of the area. I wanted to know what they had to say about it all and what they had seen over the course of their lives.

Photo of downtown Welch in 2004 when its population was around 2500

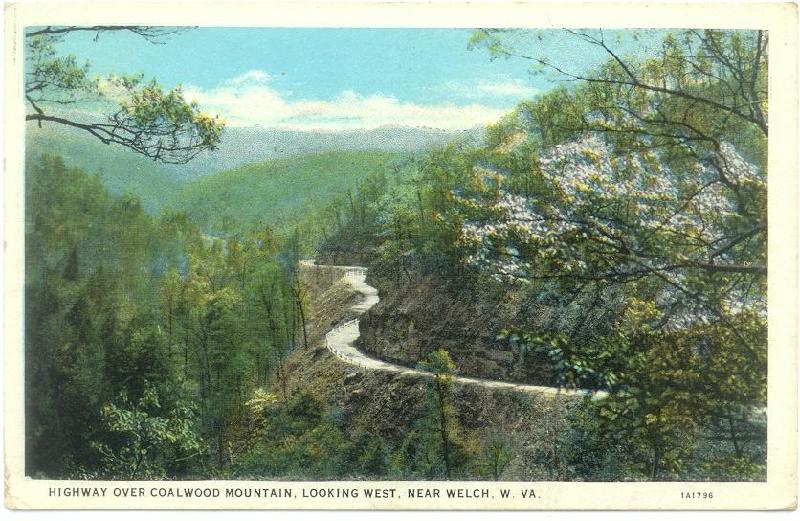

My drive into Welch (pop. 2406 in the 2010 census, estimated to be 1904 in 2019), McDowell County’s seat, is a long one, and what’s most striking is that the last two hours of it are nothing but turns on windy country roads surrounded by mountains covered in the lushest forests I’ve ever seen. I’d read a lot about this place, but nobody ever mentioned its natural beauty—or what a hassle it is to get to.

I arrive late on a Saturday and figure my best starting point is the bar I can walk to from where I’m staying. It’s small and largely unadorned. There’s a separate room full of slot machines, and everyone’s in there except me and the bartender.

I do my best to chat her up, but she isn’t much of a talker. It’s clear that she isn’t suspicious of me or anything, she’s just shy. After disappointing me for the sixth time with a one-word answer, her face brightens and she says, “I know someone you can talk to!” She walks into the gambling room and comes back with another woman.

She’s a school teacher, and has been her whole adult life. She’s happy to speak with me and says she’s used to it: journalists always seem to be streaming in and out of McDowell County. What really strikes me about her is something I’d get used to over the next few days: She’s perfectly open about the area’s decline and its many problems, but takes it all in stride, and is genuinely proud to be from here. Most of all, she’s authentically optimistic.

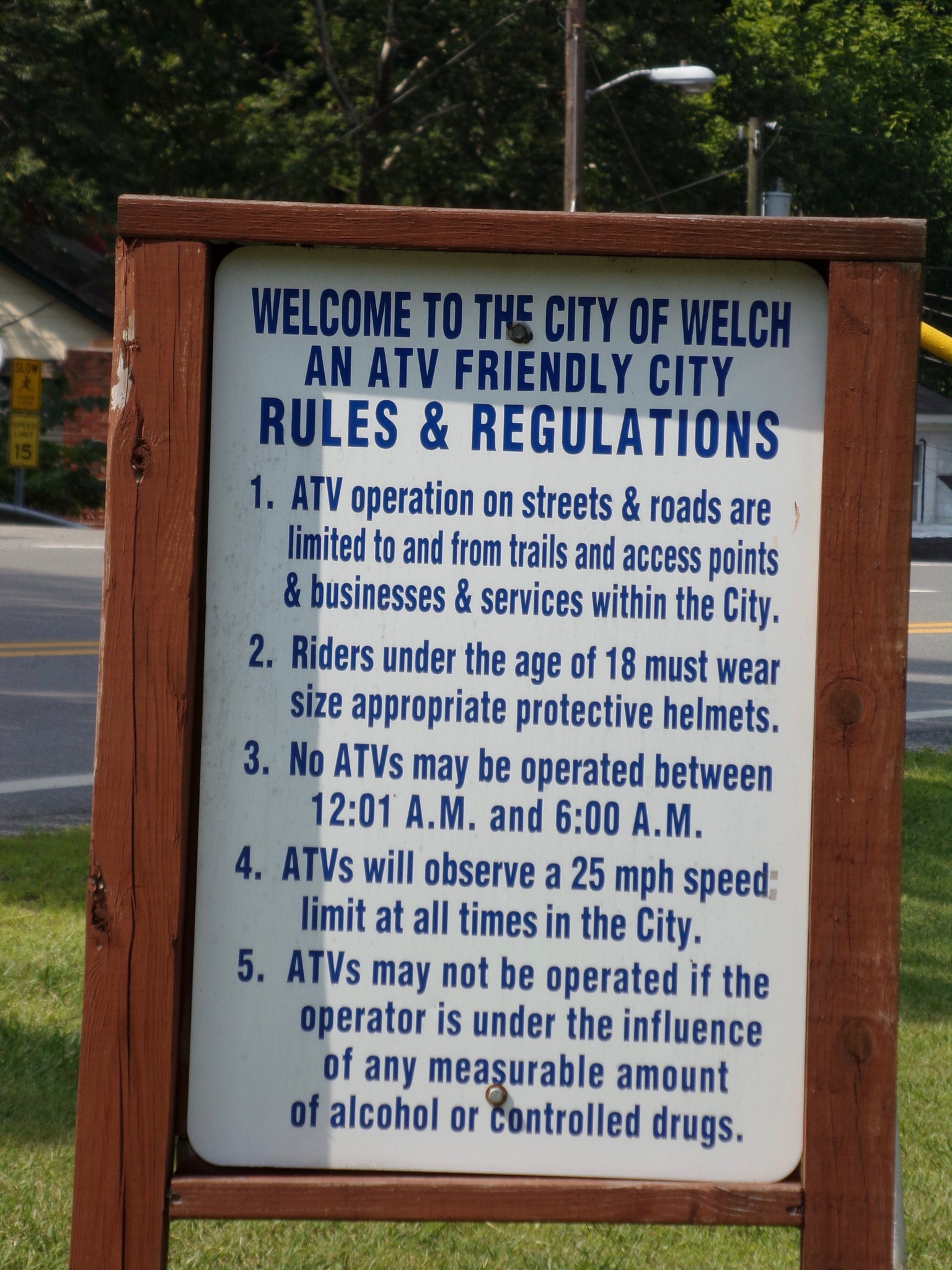

“It pays to be poor,” she jokes about the money McDowell has started getting from government and charity alike. That line, more than anything else she said, captures the duality of frankness and hope that I’d soon find in nearly everyone in southern West Virginia. She grew up in Welch and says that when she was a kid, nobody ever had to leave the city—it had everything: supermarkets, department stores, car dealerships, etc. You don’t have to spend more than five minutes downtown to know that hasn’t been the case in a long time. There’s plenty of bad, and that is what outside journalists love to focus on, but there’s plenty of good, too. This teacher tells me all about both in one big cascade of information: More than the drugs and coal mine closures, what really sent Welch spiraling were the two devastating floods in the early 2000s. But now, there’s a growing tourism industry, especially ATVers making the most out of the rough terrain. There will be more and more of that in the coming years, and that means jobs and money. The Walmart in McDowell County closed five years ago and it was devastating. Now the nearest one is at least an hour away. But now retirees are moving to the area for the low cost of living, which is more good than bad.

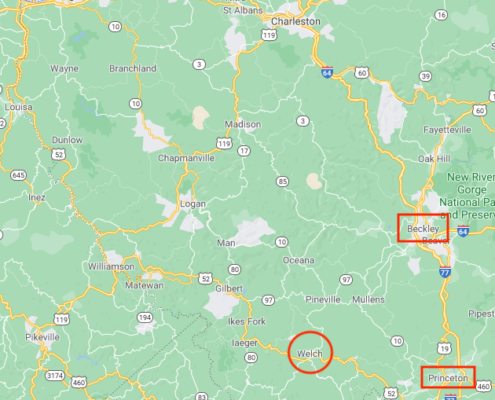

The small-town vibes are strong. She tells me people were really excited when a McDonald’s opened up in the area, and they feel the same about a Taco Bell expected to arrive soon. School activities here are a big deal both because there isn’t much else and because everyone wants to make sure the kids are alright, that their future won’t be defined by the area’s current problems. There’s nostalgia mixed with bitterness, too. Generations ago, this county was an industrial hub with ~100,000 residents. (Welch even used to be nicknamed “Little New York” and had a population of around 6000 in the 1940s.) Today the county has around 20,000 residents and is best known as the epicenter of the opioid crisis. “We built West Virginia. Now the state ends at Beckley (over an hour northeast of Welch),” she laments. “I miss seeing people I know,” she concedes. Later on, she says that people (like her sister) who left the area and came back don’t recognize it, and joke that those who never left “stayed too long.” But at the same time, she never insults this place or its people. She gives me a long list of people to speak to and sings the praises of each of them. It’s clear she doesn’t think the decline will last forever. She brings up that there’s a plan to connect a four-lane highway to Welch, and that this could bring all the uplift they need.

Downtown Welch in 1946, population ~6000

As a city-slicker, I find her optimism really striking. It isn’t forced and she’s got a list of reasons to back it up. I’m used to urban ghettoes where nobody thinks anything will get better and where apathy is so pronounced the question of whether the area will improve doesn’t even really make sense to ask, much less answer. All my life, liberals have told me that poor Whites are just as pathological as poor blacks, and that the dispossessed residents of Appalachia are just as violent and dysfunctional as the citizens of Chicago’s Southside. Walking back from the bar, I chuckle thinking about how I could go into 100 bars in Black ghettoes and never have one conversation with a local about the area as pleasant as the one I just had.

On Sunday morning I walk to a Catholic church. The service isn’t very noteworthy. Like just about anywhere else, it’s sparsely attended and the folks in the pews are almost all senior citizens. What did surprise me was the priest: A man from India with an accent. I wonder how he ended up all the way out here. After the service, one of the parishioners comes up to me with a big smile and asks where I’m from. “It’s that obvious?” I joke, because it is, of course, very much that obvious. We both laugh and I explain that I’m a journalist interested in southern West Virginia. We exchange phone numbers and agree to meet and talk later in the week.

I’m a sucker for diners, so after church I open up Google Maps to find the nearest one. In what I became resentfully accustomed to over the course of the week, I discovered that the nearest place was about an hour away. I drive to Dolly’s Diner in the city of Princeton, which is in neighboring Mercer County. Again, the drive feels like a series of switchbacks and blind curves surrounded by tree-covered mountains. When I get there, the restaurant is in the midst of its “post-Church rush” and I’m seated immediately only because there’s a lone stool left at the very end of the bar. Everyone (staff and clients) is White and about half the men are wearing baseball caps. There’s a real “grandparents and grandkids” energy to the place. Though there are certainly exceptions, you can immediately tell that there are plenty of absent parents in these families. Last night, the school teacher had told me that not only are there lots of people raising their grandchildren around here, there are even some people raising their great-grandchildren. The décor is what you’d imagine: Americana, cars, “In God We Trust,” etc. They sell Christian keychains from the Child Evangelism Fellowship. At the cash register there’s a notice for the “20th Anniversary 9/11 Stair Climb.”

As I write all of this in my notepad two waitresses take notice and ask me (without a hint of suspicion) what I’m doing. I tell them I’m visiting the area from a long way away and taking notes. They like that answer and I take the opportunity to ask them what they like best about the place. They both say the natural beauty and the kindness of the people here. They say that people everywhere else are mean, even hateful. One mentions having gone to South Carolina only to discover that everybody there was rude. On cue, a man paying out at the register near my seat welcomes me to the area and wishes me the best with a big smile before he leaves.

When I get going, I think about the prospect of a major highway making its way to McDowell County. I’m near Highway 77, and it seems to have done well by the area: There’s Starbucks, Lowe’s, Outback Steakhouse, Radisson, Applebee’s, etc. It’s easy to shrug off those chains as shallow or uncultured, but they’re sure better than boarded-up storefronts—and they’re probably the same chains you find where you live. The American monoculture.

Back in Welch, I wander around town for a bit. I’ve lived all over the United States, but always in cities. The texture of life here is different. The internet is bad and cellphone reception is weak. There are plenty of pharmacies and churches, but not much else—though importantly, there’s not nothing else. What I notice most is that unlike in ghettoes, here, nobody is milling about looking for trouble. There aren’t layabouts loitering in front of any place that sells liquor. The parks aren’t filled with rowdy teens hoping to find a fight. And despite the area’s notorious drug problem, I don’t run into any toughs sitting on a bench or pacing around an intersection waiting for their customers. In every ghetto I’ve ever been to, it’s been easy to spot who’s hustling. Here, most everybody seems to be inside. I wonder if it’s all done behind closed doors.

Welch government building

Later I get a bite to eat at a KFC. There’s a couple in their sixties having dinner and I ask if they might give me an interview. They agree, completely nonplussed. Their answers are almost exactly what any liberal journalist might have made up. Both love Donald Trump, but have never voted. Both thought about registering to vote just because they thought Mr. Trump was so great, but failed to do so in both 2016 and 2020. They think they will when he runs again in 2024. Both say the drug problem in the area got bad about twenty years ago and that they know many people who have overdosed. It’s clear they don’t want to go into details about that last part, and I don’t push it. He’s a retired coal miner, and not only were both his father and his grandfather coal miners, but two of his sons are as well. I tell them that, as I drove around today, it seemed like every two miles I saw a sign that said “ATVs Welcome” or some kind of ATV-related business. He told me that it’s all the rage now because that’s where the money is, but that it’s a relatively recent development. The three of us chat politely for a while. Before they leave, he gives me directions to their home and tells me that this way, if I have any car trouble near him, I’ll know how to walk to his place so he can help me. His generosity and trust really floor me. I immediately think two thoughts at once: What those waitresses said about the people around here, and that in any ghetto, a car breakdown can cost you your life.

ATV Stop Sign

That night, I decide to go to another bar and see what more locals will tell me about the area. Once again, I find that there are slim pickings out here, and I end up driving the hour back to Princeton. Just like in McDowell, you can still smoke cigarettes inside bars in Mercer County. While I certainly enjoy it, it’s yet another thing that can give this part of the country a “land that time forgot” feel. In Minnesota, where I grew up, smoking in bars was banned some 15 years ago.

I meet a nice young couple who are clearly bright, progressive, and rather hip. He studied political science at the University of West Virginia in Morgantown, several hours north, and he’s very happy to talk policy with an outsider. My notebook gets filled in no time at all as I chain-smoke and he gives me his opinion on absolutely everything pertaining to West Virginia.

Perhaps I’m a jaded right-winger, but despite his obvious intelligence, some of what he says strikes me as naïve. He thinks all drugs should be legalized, and that removing the “stigma” of drug addiction would go a long way in solving the opioid crisis. I have a great deal of empathy for addicts, but there’s never going to be any way of removing the “stigma” around a class of people who will lie, steal, and take advantage of those closest to them in order to get a fix.

The point he hammers home most, however, is infrastructure. He brings up that in southern West Virginia, there are a lot of jobs in prisons (and the teacher I met on my first night said that education and healthcare provide the most employment for the area), and while those jobs aren’t great, they aren’t terrible, either. Perhaps best of all, they don’t despoil the environment the way the extraction industries do. He brings up how building a highway into McDowell would be a tide that lifted all boats. First there would be a wave of construction jobs, those men would then spend more money locally, and then the highway would make accessing the area easier, so more businesses would inevitably arrive. It’s not just big projects that are necessary, though. He tells me that plumbing is so bad in some of the more rural areas that people catch water runoff from mountain streams. He also brings up what many people are talking about now—that COVID changed everything: Since working from home is becoming the norm, people are going to move to cheap areas. West Virginia can reap the benefits of that enormously—but only if highspeed internet becomes more widely available.

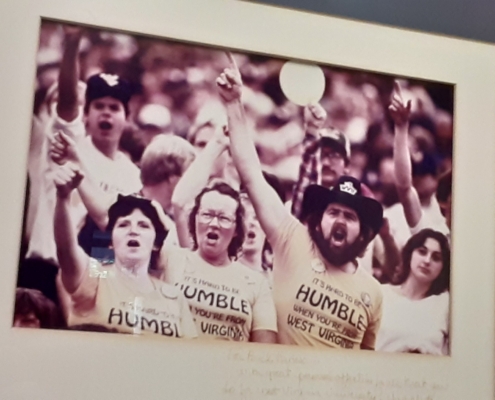

Stevens Correctional Center

I tell him that I’ve been surprised at how everybody I’ve met around here seems proud of their state and their region, and that I haven’t found that to be the case in other poor areas. He and his girlfriend are especially interesting examples of this. It seems like almost every young progressive I’ve ever known hates where they’re from, can’t wait to leave, and loves to talk trash about wherever it is that they grew up. He laughs a little and says that since everyone else insults West Virginia, West Virginians refuse to do so. His girlfriend agrees, and he talks about how in the southern part of the state there’s a real sense of community and solidarity. In the public schools I attended in St. Paul, students were lectured constantly about “community.” The school was a community, gays were a community, the disabled were a community, the planet was a community of nations, we should all go to college and get jobs helping our “communities,” etc. It always felt so forced, so manufactured, that by the end of high school I thought I’d developed an allergy to the word. In college I knew a liberal who once told me he had an ex-girlfriend who was “active in the rave community.” But here, in West Virginia, the word actually seems to carry some freight, have some tangible implications.

It’s Hard to Be Humble

Like everyone else I’d met, he wasn’t shy about the area’s problems. He has known people who died from overdoses, and said I wouldn’t find anyone who could say otherwise. But he was confident that the worst was behind the state, putting the grimmest year at 2017 or 2018. In my notes, I wrote, “Hope and Empathy in Southern WV” (vis-à-vis) “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.”

On Monday morning I went to an ATV shop in Welch and spoke with one of its owners. Incredibly, in the middle of the day he spoke with me for over an hour, pausing only a handful of times to attend to customers. He grew up in the area, and like everyone else who did, remembers its former glory, saying that when he was a kid, going to Welch on a Friday evening beat going to the beach on Saturday. He left the state in 1994 and says that at that point, the decline was apparent but still not bleak. He came back in 2013 and things had gotten much worse. His comments mostly fit the pattern I started noticing early on: Things are bad, but things are getting better—especially since the people who live in the area are the best folks you’ll find anywhere. “I know what was once here and I know it can come back,” he says. He’s a bit biased on the subject, but like everyone else, the growing ATV/tourism industry gives him a lot of hope.

ATV Rules

Like the young man from the bar the night before, this guy explains how in southern West Virginia, the tourism industry and the extraction industries are locked in combat. Nature preserves and hiking trails create “no-go” zones for mining and lumber companies, so the latter fight hard against the creation of the former. Extraction brings in more money than tourism, but the resources they’re pulling out of the ground can’t last forever—tourism can last forever . . . so long as nobody destroys the area’s natural beauty. With no disrespect intended to the area, I can’t help but note that this same economic tension can be found throughout Latin America.

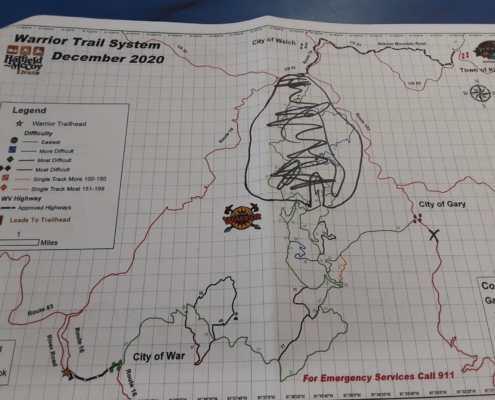

Warrior Trail System. On this trail map, my informant used a black sharpie to show me how much had recently been closed at the behest of one extraction industry or another.

At one point his wife comes in and asks me pointblank if I’m an honest journalist. I say that I am, but admit that if I wasn’t, I wouldn’t say as much. She gives me a look and I assure her that I intend to quote everyone anonymously, which seems to mollify her. He then shares some horror stories with me about liberal journalists coming into town and making the area sound like a hellhole of poverty and stupid rednecks. I tell him the truth: That to my surprise, everybody here has a real dignity to them, and that their optimism seems based in reality.

Later on, a customer comes in without a shirt on and his chest sports a tattoo of Psalm 23—the one most famous for its line about the “valley of the shadow of death.” In the next few days, I bump into Psalm 23 again as a poster in a government office and another in a private dwelling.

I ask him about the drug crisis and he says, “We have a long way to go.” He shares a heartbreaking story about a woman in her late twenties who’d been clean for years until relapsing eight days ago. She died. “You just wait on that phone call,” he states flatly.

There’s a food bank across the street and I pop in to see if I can speak to one of the volunteers. Again, despite it being in the middle of a work day, I find someone who’s happy to set aside some time to talk to me. She’s a woman in her thirties from neighboring Wyoming County. She tells me upfront that she wants to talk only about the positive. We talk for a while about the logistics of her food bank and her high opinion of the mayor (the man at the ATV store said the same thing). Her recommendations for improving the area are fairly standard: better public transportation, a rehab center in Welch itself (not just relatively nearby), bringing down the high-level drug dealers, etc. By now I already feel like I’ve heard this a million times, but she tells me that it was the devastating floods of the early 2000s that really brought down Welch, much more so than the drugs the national media prefer to talk about.

Welch, WV, May 9, 2002 —The Dollar General in Welch, West Virginia lost its complete inventory the second time in two years due to the May 2, 2002 flash flood.

Bob McMillan/ FEMA Photo

She tells me that, “I wanna see us be something,” and believes the drug problem is getting better, placing the worst of it at around 2018 or 2019. By now I had already heard several tragic stories about fatal overdoses, but when she tells me her husband died in March (without specifying the cause), it hits me harder than any other death I’ve heard about. She’s now a single mother of three, and still volunteers at a food bank. She admits to having thought about suicide, but that “God keeps me going.” She says she cries at night, not during the day. The last thing she tells me is that “McDowell County is a good place; it’s a whole lot more than we get credit for. We’re trying to get somewheres.”

I doubt if I’ll ever be able to convey this without sounding condescending, but there’s a noble durability to the people here that I’ve never encountered before. We’ve all faced hardship. I’ve known people who committed suicide and people who died from overdoses. The 2008 economic crash hit my family hard, too. But like with most things, hardship is a question of scale. The scale of grief so many of these people have endured is like nothing I’m familiar with. And yet they all seem happier, friendlier, and more optimistic than I am. Some might say I’m making “noble savages” out of the residents of southern West Virginia, but that’s not it. There’s nothing savage about them. Savages shoot at helicopters trying to evacuate hospitals because of a natural disaster. There’s nothing savage about volunteering at a food bank or running an ATV shop. I’ve lived in ghettoes before and seen plenty of savagery. Savagery is a gang of teenagers beating a pregnant woman to the ground. I’m still new in town, but it’s hard to imagine that happening in McDowell County.

I have a late lunch at a restaurant in Kimball, just a few miles from Welch. More than one person recommended that I speak to the woman who runs the place, another lifelong resident. She’s as friendly as everyone else and confirms a lot of what I’ve been hearing: It was the floods that really marked the beginning of the decline, there’s hope in the tourism and the incoming retirees, she remembers the good old days, etc. The mix of hope and frankness is as present in her as in anyone I’ve spoken to: “If ATVs are our lemons, let’s make lemonade. Will it be our salvation? Probably not.” If anything, she’s somewhat more frank than hopeful. I tell her I really appreciate her honesty when she concedes that bringing back jobs isn’t as simple as building new businesses, because plenty of people in the area no longer want to work. She has more insight about the economics of the area than anyone else I’ve met, noting that Walmart came to town, ran everyone out of business, and then closed down. These are the kinds of stories that one day might just make a liberal out of me. She also tells me that a joke I’d heard earlier is actually a known saying: Out here, after high school, you’ve got four options: college, military, mines, or fast food.

McDonalds hiring: $10 Per Hour

She’s a first responder as well as a restauranteur, and it’s clear she’s seen a lot—and she wishes young people could see her dealing with the overdoses, the car wrecks, and the misery of it all. Her first year in the field was 1985, and she says this past year was the worst one she’s seen, likely because the COVID-related increase in welfare handouts gave a lot of unhealthy and unhappy people more money to spend (a few days later, a local journalist confirms this). As I write that, I realize that everyone I’ve spoken to has put the worst year at one or two years more recently than the person before. The millennial at the bar said 2017 or 2018, the woman at the food bank said 2018 or 2019, and this woman is saying 2020.

“Our people have some of the biggest hearts. If you have a problem, it’ll be a problem for everyone,” she tells me. She follows that up with a story from her time as a college student in New York City. Once, she was on the subway with some peers and saw a man have a seizure. She was the only person who ran over to try to help him. Not only did her fellow students do nothing, they told her she should stop trying to help because it could be some type of scam or setup. Perhaps the man was faking it so that he could pickpocket whoever came to his aid, or something like that. She told me that she still wonders about that day, if she should have done more because it was a real medical emergency, or if she should have done nothing at all. Apparently, people have told this woman to her face that she likes McDowell County only because she has no point of comparison. This is the story she always shares by way of reply. That kind of conundrum is unimaginable here.

At the risk of belaboring a point, this woman has seen more devastation and heartache than I probably ever will. But her story about New York City is very meaningful. The Big Apple has plenty of drugs and suicide, too. But the coldness of its people (which I’ve encountered firsthand) is a type of alien cruelty that’s inconceivable here. This wasn’t something I’d thought about at all when I made plans to come here.

The next person I speak to is an elected law enforcement official gracious enough to give me an interview. Police are normally leery of journalists, but this guy makes it clear he has nothing to hide. We talk about crime, of course, but more specifically, why it is that McDowell County has relatively little crime. “Experts” love to explain how poverty causes crime, but if that’s true, southern West Virginia is quite an outlier. He tells me that McDowell County averages one murder a year, although there were three in 2020, and that basically all crime is drug-related: possession of drugs, distribution of drugs, and theft/burglary to buy drugs. Despite that, people here don’t feel the need to always lock up their homes and their cars, and he notes that there’s nowhere in the whole county where someone would fear for their safety if their car broke down.

I ask him what he thinks could be done to fight the drug crisis and he doesn’t hesitate to tell me that tougher sentencing is needed. “Holding jail terms over people’s heads is good,” he says. He talks a bit about how demoralizing it is to bust dealers and see them back in the streets only a few years later. Moreover, lighter sentencing has made it harder to get low-level arrestees to become informants or just squeal on the people above them in the food chain.

When I bring up tougher border security as a way to cut back on the flow of drugs, he agrees that it would help, but stresses that focusing on the southern border would not be enough. He wants to see better screening in the ports on the East Coast. Some have suggested that federal agencies, like the DEA or ATF, should come into the area to help stamp out the opioid scourge and I ask him if he thinks that would help. He says it could, but circles back to the issue of light sentencing. He points out that even if the FBI came in, all their expertise and resources wouldn’t make a difference if the people they bust still had to serve only a year or two in prison.

He’s the first person I speak to who is unwilling to say that things are definitely looking up: “I would never say the worst of the worst is behind us.” But like everyone else, he says the region’s citizens give him hope: “They’re not gonna give up.”

That night I get dinner at local restaurant in Roderfield, about ten minutes from Welch. Like the diner in Mercer County, its decor is solidly Christian Americana. The waitress is nice and clearly surprised that I want to speak to her about her own life, and life in general in this part of the country. She’s the first person I meet who isn’t from here. She grew up in a Buchanan County, one of the poorest parts of Virginia. With the help of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, she got an apartment nearby, believing there were more jobs in this area than in her home town. She concedes that she didn’t know how bad things were in McDowell when she came here. All the same, she’s done well for herself. She has a serious boyfriend and they want to move to Tennessee. She tells me she’s never been tempted to use drugs and doesn’t have anyone in her social circle who uses. She is very surprised when I tell her I think I would be tempted if I lived here. (To be perfectly honest, throughout my teens and early twenties, I partied a lot—with all the drug use that that implies. It’s grim to admit, but I’m not sure I would have made it past 25 if I’d grown up here.) She has more than a few horror stories of the kind you can easily find from other reporters who focus on the area’s dispossession, but she doesn’t want me sharing them. However, she is the first person to tell me that the drug crisis is getting worse, not better. When I ask her what she wishes outsiders knew about McDowell County she says, “I don’t know, I honestly don’t.”

God’s Corner

The next morning, I interview the mayor of a town in McDowell County. Both he and the employee who makes our conversation happen are very clear that they don’t want to talk to me if I’m just going to write yet another sob story about how awful the area is. They’ve had plenty of journalists come through and pen bleak writeups about how miserable everyone in McDowell County is, and they hate being portrayed that way. I tell them that so far, just about everyone I’ve interviewed has been optimistic, and the area isn’t nearly as rough as I’d imagined. With that, the government employee gives me a useful list of people to speak with, and even makes an introduction or two.

The mayor is by far the most optimistic citizen I’ve spoken to. He says he has “no clue” why the area has a bad reputation and that “crisis” is too strong a word for the drug problem, the worst of which has long gone by. “Every place in the whole world has that issue,” he insists. While that’s true, it’s also not that simple. He talks a very big game about tourism, saying that the area can become another Dollywood, but he’s not building castles in the sky. He’s smart enough to note that although visiting dads will be happy to ride ATVs all week, the area needs to build things for mom and the kids to do: fishing ponds, ziplines, amusement parks, etc. Over and over as we talk, he says his boundless optimism is rooted in the goodness of the citizenry: “People are our greatest advantage,” “We’re a frontier that can make anything happen,” “We’re on the move and we’re gonna keep moving,” “We have the mentality there’s nothing we can’t do,” etc.

ATV Resort

If I had met him on my first day, I’d have taken him for a total Pollyanna. But after speaking with so many locals, I can’t see why anyone shouldn’t have faith in this place and its people. His optimism is maybe a bit much, but he is, after all, a politician talking to an outsider (though, for the record, he did tell me unequivocally, “I don’t consider myself a politician”)—and he’s not wrong when he says a positive attitude at the top is necessary because it will filter down to everyone. When I push him on how strange it’s going to be for a region to transition from an industrial juggernaut to a tourist hamlet over the course of living memory, he admits that I’m right. But he won’t let that weirdness get to him. If that’s the change that needs to happen to keep the place afloat economically, then that’s what needs to be done. Like the restauranteur, he says something about making lemonade out of lemons.

On my way out, a government employee, presumably familiar with the mayor’s can-do attitude, reaffirms that this place really isn’t so bad, it’s not all drug addicts and desolation the way the mainstream portrays it. I tell him he’s right (because he is) and note that I have yet to hear gunfire—and I’ve lived in places where you hear it pretty often. “Oh, you will in hunting season,” he replies, grinning from ear to ear.

My next stop is another food bank. The woman who runs it was hesitant to speak with me, but by this point had already heard from other locals that I seemed alright. When we meet, she is absolutely insistent that I better not spin a tale of doom and gloom. She says that if I’m going to do that, I should leave, and that she has kicked journalists out of her food bank once it became clear they were just looking for sob stories. I swear up and down that I’m going to write honestly about what I find, and that so far, I’ve found more hope than anything else.

Playground mural

Perhaps I’m repeating myself to the point of tedium, but this woman, like so many other people out here, is a fascinating mix of brutal honestly about the area and indefatigable pride in its people and hope for its future. My notes from our conversation are a Jackson Pollack painting of this dialectic. She tells me that, “People let their hurts take them to the grave,” but, “I want to speak life into people.” She gives me a stern look and says, “Don’t think I don’t cry,” but that “every day is a new day.” More than anything else, she talks about choice. Eve had a choice in the Garden of Eden, and people here have a choice, too. She can’t stress the matter of choice enough, and it’s clear that for her, that’s the big source of hope. Addiction and despair are choices, not destinies. With choice, the future remains unwritten. I’m not convinced it’s as simple as that. But this woman is a force of nature. Her food bank is massive and it’s entirely privately funded. She shows me around and it’s well-stocked, to put it mildly, not only is there food but there’s school supplies, toiletries, just about everything, really. I’ve lived a life of privilege compared to this woman, but she’s the one doing God’s work. It doesn’t really feel like she’s given me any choice about feeling impressed and humbled.

I spend the afternoon driving around, trying to get a better feel for the area and hoping to find more people to interview. McDowell County isn’t especially populous, but it’s still huge: 535 square miles. Atlanta, one of the most spread-out cities in the country, is just 134 square miles. Every store here (restaurants, gas stations, pharmacies, etc.) has a sign advertising that they sell passes for the Hatfield-McCoy Trail, the main tourist attraction.

I make it to Bradshaw, which many people in Welch seem to consider the more rural, more redneck part of the county. I didn’t get that sense, but it’s certainly poorer than just about every other town I’ve visited. I try to go to a town called War next, but my phone loses all reception and internet connectivity. I get hopelessly lost, and honestly, War might be so small that I drove through it and didn’t notice. When I finally figure out how to get back to Welch it starts pouring rain, and with the roads being as curvy and narrow as they are, with no shoulder to pull off onto, for a few minutes I wonder if I’m going to make it back in one piece.

I make it to Bradshaw, which many people in Welch seem to consider the more rural, more redneck part of the county. I didn’t get that sense, but it’s certainly poorer than just about every other town I’ve visited. I try to go to a town called War next, but my phone loses all reception and internet connectivity. I get hopelessly lost, and honestly, War might be so small that I drove through it and didn’t notice. When I finally figure out how to get back to Welch it starts pouring rain, and with the roads being as curvy and narrow as they are, with no shoulder to pull off onto, for a few minutes I wonder if I’m going to make it back in one piece.

Bradshaw Economy Drug

Empty Bradshaw Building

When I get back to where I’m staying, I’m so exhausted that I take a nap. I’m probably just an ugly outsider for saying this, but I really have no idea how people here deal with these roads, especially since you need to drive to get anything. A few hours later, I drive to Pineville in neighboring Wyoming County and step into the Ole’ Jose Grill and Cantina. It’s the first complete tourist trap I’ve been to out here. Everyone inside is an ATVer, and the restaurant has a generic, antiseptic atmosphere that I can’t stand.

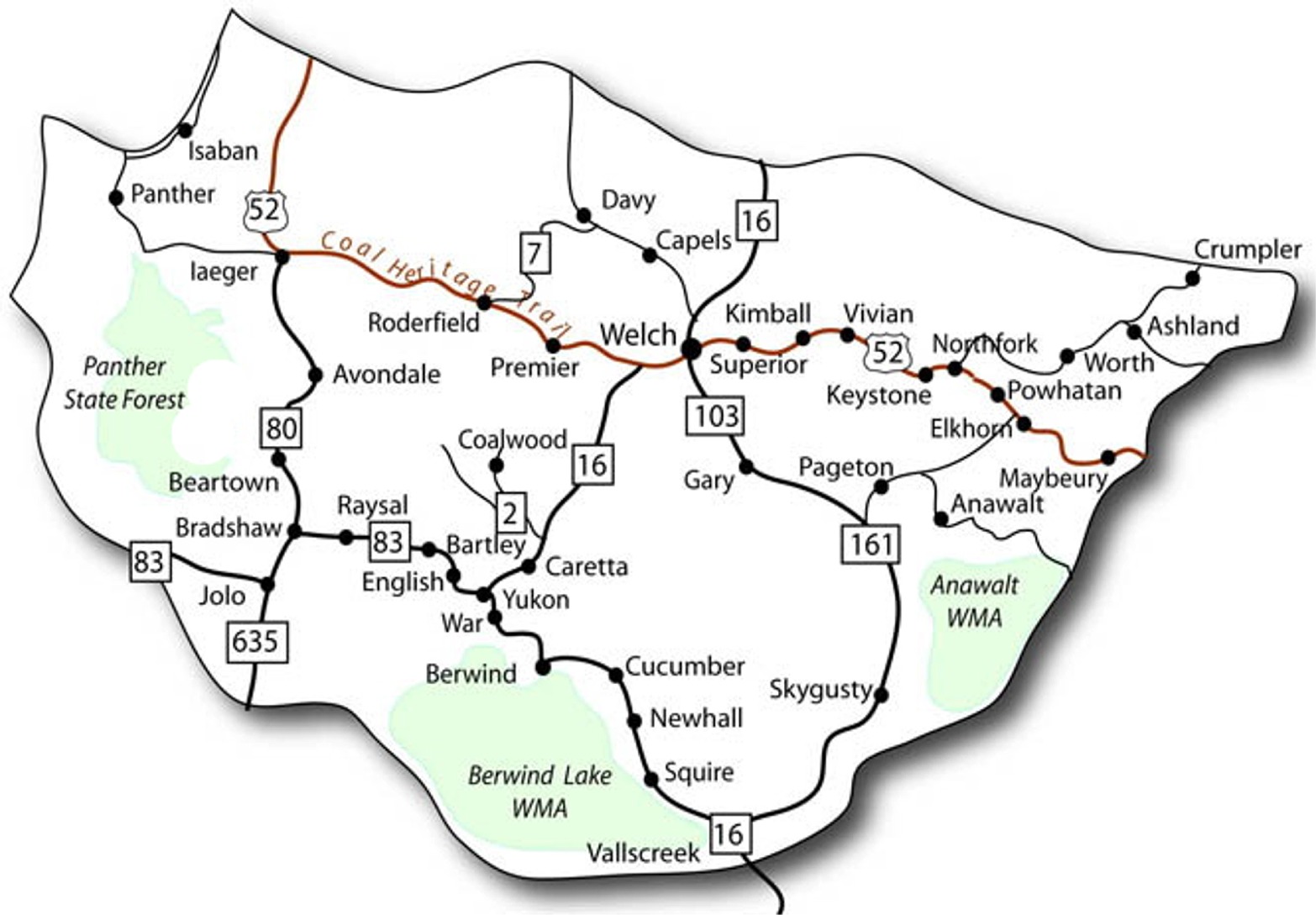

Map of McDowell County

Back in Welch, I walk down into a valley of sorts behind a row of apartment buildings. There’s a big park with a pool, basketball courts, etc. Southern West Virginia has a reputation for being solidly White, but McDowell County is actually almost 10 percent Black. At the pool, it suddenly feels like I’m in a big city again. Everyone there is Black except the White lifeguards. Unruly kids are running around everywhere, it’s loud, and not just because someone is blaring rap from a set of speakers. One guy is driving his ATV back and forth on a little pathway, making all kinds of racket. The smell of marijuana is unmistakable. I wasn’t born yesterday, so I leave. The Whites I’ve met here aren’t much like Whites I’ve met elsewhere, but the texture of Black behavior is always the same. See, for example, this music video made by some of the area’s aspiring rappers. I believe it was filmed in one of the apartment buildings near this pool.

That night I go to interesting local business in Welch. By day, it’s something of a family restaurant with pizza and burgers. But it’s also got a bar you can smoke at, and an adjacent enclosed room filled with slot machines. I get a sandwich and some coffee and start chatting with the White girl working the register, who’s just a few years younger than me.

She’s impeccably sweet and all too happy to pass the time with someone new. She volunteers her life story with little coaxing. It’s intense, to be sure. There’s drug use, illegitimate children, legal trouble, etc. And yet, her positivity shines through it all. She plans on staying in the area because it’s where all her family is. Moreover, the people here are great. Earlier that day, she’d gotten a flat tire and found help in no more than 15 minutes. “It’s boring [here], but help is always just 15 minutes away,” she observes.

Doors of a Welch Pharmacy

Much of what she says I’ve heard before at this point: The floods were the beginning of the end, the tourism industry is a sign of hope, that the loss of the local Walmart was devastating, that not only is there a need for more grocery stores but for social spaces as well (arcades, bowling alleys, etc.). I ask her if working where she does has made her think gambling should be banned. While she admits that she sees plenty of people spend way too much time and money at the slots, she notes that the thrill people get from gambling is still much better than the ever-present alternative for thrills: drugs. She follows that up by pointing out that if addicts lose all their money gambling, that’s just less money they can spend on poison. That perspective is cynical, but she might be on to something.

She can’t say for sure when the worst year of the drug crisis was, and isn’t willing to say that the worst of it is over. I wonder if that’s informed by her own past drug use. At the end of the night, her own version of the area’s signature blend of pride and pessimism gets especially intense. She says she wishes outsiders knew that people in McDowell County are normal, not shoeless hillbillies. When I ask her for her best prediction for what the area will be like in 40 years, her answer startles me: She says by then, there might not be anything left, that everyone will have died or left. Even still, she says, “if the apocalypse comes, I’d still rather be here than in a big city.”

I’ve never been religious, but that night I talk with some devout New Englanders who live near where I’m staying. They came to the area on an uplift mission and ended up staying and starting a family. The husband tells me with no hesitation that if he were an atheist, he’d be cynical about the area and have left long ago. But he isn’t. Moreover, he says it’s the people here who teach him about God, not vice versa. On top of that, he tells me that the misery these people have endured is spiritually redemptive, and that God will reward them for it in the next life. I can’t help but find a certain logic to this. These people have every reason to be angry, and could come up with a long list of excuses for self-destruction and nihilism, but none of that is in play here, at least not in an endemic way. It’s hard to know exactly what to make of it.

Old Country Church

The next day I drive, sharp turns all the way, to a rehab center in neighboring Mingo County. It’s a live-in place for women only, and the staff is kind enough to let me anonymously interview any resident willing to talk to me. I speak to three women back-to-back over the course of about an hour and a half. It’s a gut-punch that leaves me reeling and desperately wondering if I just crashed up against a brutal reality-check. I’m not unfamiliar with people who have messed up families, broken marriages, and checkered pasts, but these three women’s stories are on another level. I don’t want to indulge in “pity porn” or make them feel like their privacy has been violated, so I’m going to skip the gory details.

But more than the hell they’ve all been through, what gets to me is how they answer my questions at the end of each interview. Not one of them said there was any reason to think things will get better. Not one was willing to say the worst of the drug crisis was in the rearview mirror. In short, they all said things will only disintegrate further, and that everyone who’d told me otherwise was out-and-out lying to me, lying to themselves, or both. Here are some quotes from the three of them:

“It’s more than a crisis.”

“It’s only gotten worse so far.”

“The [types of] drugs will change but I don’t think the scenario ever will.”

“These other people are feeding you some bullshit.”

“It’s only going to get worse.”

“I know if I were on drugs, I’d feed you a bunch of bullshit. Just being honest.”

I drive back to Welch wondering what on Earth to believe. I return to the bar I went to my first night in town and can’t help but tell the first person who will listen about what I just heard. She tells me the women at the rehab center may well be right. She grew up here, left, and came back. She’s struggled with addiction and still hates the doctors who got her started. “I’m not supposed to be here,” she says, and tells me she’ll be leaving again when she gets the chance.

Staying at this bar and knocking back more beer is not a good idea, so I leave to meet up with the religious New Englanders I’d met a few days ago. Almost as if the whole day has been scripted, the wife tells me she can’t imagine enduring all this chaos without trusting fully in God’s plan. That’s not just the opinion of an outsider, either. Most of the locals here seem to feel the same way. Not all of them, of course, but a lot of them. The Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky once said, “If someone succeeded in proving to me that Christ was outside the truth, and if, indeed, the truth was outside Christ, then I would sooner remain with Christ than with the truth.” Everyone in this part of the country is a thousand times more resilient than me. That sounds corny, but it’s true. And their faith is a cornerstone of that reality. It occurs to me that my atheism has nothing to offer people here, but that their God, with his courage, forgiveness, and long view, has a lot to offer me—regardless of whether he exists. What’s more is that my lack of faith isn’t slowing anybody down out here, but their spiritual confidence really does give me a sense of hope. It was just the other day that the male half of this couple told me the locals teach him about God, not the other way around. The faithful have crises of faith, but what’s discussed less often is that atheists have crises of disbelief. In that moment, I started to feel like a character in a Flannery O’Connor story who sees the grace of God just before some gothic horror strikes them.

Over the course of my last two days there I do a lot more driving. I visit all the cities closest to Welch that people have named as the best places nearby: Tazewell, Virginia; Bluefield, West Virginia; and Beckley, West Virginia. Tazewell is cute; an interesting mix of God’s country (unvandalized Confederate monuments, MAGA signs, and motorcycles) and the kind of bucolic small town our liberal elites love to vacation in (local brewery, pricey coffee shops, and a fancy brunch spot). Bluefield is a bigger, less poor Welch. There are boarded up shops right alongside nice office buildings. Beckley is like one of those mid-sized cities you stop to get gas in on a road trip. It’s perfectly pleasant and middle-class, but doesn’t have much character. I go to a few museums about mining and feel much more like a tourist than a journalist.

Tazewell Confederate Monument

Bluefield Office

Empty Bluefield Building

When not meandering, I spend much of my last 48 hours with two fascinating Welch locals, a woman in her fifties and a man a few years older than me. They’re the smartest people I’ve met out here, and over the course of hours of conversation with them, they humble me over and over again. At her age, and having lived almost her whole life in McDowell, there’s nothing she hasn’t seen, but she’s still here, still surviving, still hopeful, and still working for a better tomorrow. He’s basically my age, but his life has been tougher than anything I can comprehend. I don’t know how he manages to share so many stories about overdoses and suicides without crying, but he does.

At the end of the week, I drive home and there’s everything to think about alone in my car for hours and hours. It’s as if I can’t even remember what I was expecting to find now that I’ve seen so much. Southern West Virginia is poor, and the stories of its heartbreak could fill the Library of Congress a hundred times over. But I knew all that before I got there—you probably did, too. However, it’s not some kind of “big White ghetto” in the midst of a Hobbesian war of all against all. I’ve really never met kinder people. I’ve also never met a people more determined to withstand it all and persevere. The place enlightened me—but only after it humbled me. All of us really do have a lot to learn from these people. Marcus Aurelius wrote that, “Nothing can happen to any man that nature has not fitted him to endure. Your neighbor’s experiences are no different from your own; yet he, being either less aware of what has happened or more eager to show his mettle, stands steady and undaunted. For shame, that ignorance and vanity should prove stronger than wisdom!” My Christian friends assure me that Christ agrees. I couldn’t tell you if God is real, but after a week in Welch, I do know for certain that God smiles upon southern West Virginia—and on the rest of us as well.

Martin C. Rojas, who died on June 24, 2022 at the age of 29, was perhaps the most brilliant, original, and prolific writer of his generation. Because of the current Reign Of Terror, he wrote for VDARE.com under the names of Chris Roberts, Hubert Collins, Gilbert Cavanaugh, Nathan Doyle, and Benjamin Villaroel, and as Chris Roberts for American Renaissance, and at Counter-Currents as Hubert Collins, Benjamin Villaroel, and Nathan Doyle.

For Jared Taylor’s tribute, see here; for Lydia Brimelow’s tribute, see here.