As I may have mentioned once or twice over the last decade, the Theory of Intersectionality proves that black women, by being the most intersectional, have the most interesting thoughts. So what have they been thinking about since 1619? Mostly, about how peeved they are that people are blind to their fabulousness. Also, their hair.

From the Washington Post:

In Paris, artist Mickalene Thomas takes on Monet, and art history itself

For “Mickalene Thomas: Avec Monet,” the American artist created works that reflect on the French painter and move Black women into the foreground

By Robin Givhan

Robin Givhan is senior critic-at-large writing about politics, race and the arts. A 2006 Pulitzer Prize winner for criticism, Givhan has also worked at Newsweek/Daily Beast, Vogue magazine and the Detroit Free Press.

November 22, 2022 at 6:00 a.m. EST… There’s only a discreet posting near her building’s buzzer to indicate that behind these industrial doors lies a magical, kaleidoscopic world of paint, paper and paillettes depicting Black women in repose, Black women indulging in the luxury of self-assurance, Black women existing in a world of their own creation.

Thomas, 51, has built her substantial art-world reputation by focusing on Black women … Thomas’s women often look as though they have stepped from a blaxploitation film, the pages of Ebony or Jet magazines, or the imagination of someone who keenly understands the importance of celebrating your own fabulousness when the world is stubbornly blind to it.

”We, too, can recline,” Thomas declares. “We, too, can relax and be seen doing so and have it be empowering and validating for our sense of self. We can be in the moment and in own our space and not be seen as being lazy.”

She’s had a multitude of exhibitions, including at the Brooklyn Museum, the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, and numerous galleries. …

Thomas’s fine art is now the subject of an exhibition that opened in October at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. The museum, in the Tuileries Garden, is known as the permanent home for eight of Claude Monet’s waterlily paintings. The exhibition organizers asked Thomas to create works that reflect on Monet and the time she spent as an artist-in-residence at his former home in Giverny, France, in 2011.

“Mickalene Thomas: Avec Monet” is her first exhibition at a museum in France. … The small museum was constructed in 1852, and over time, its collection has helped to tell the erroneous story of French art, establishing a narrative that European art is White when, in fact, it is Asian and African, too. Thomas disrupts that story in ways both obvious and subtle, by her mere presence and with her work.

Detail from “La Maison de Monet” by Mickalene Thomas.

So, she took some photos of Monet’s house, made a 1978 David Hockney-style collage out of them, and scribbled on it.

Thomas attributes the existence of her exhibition to an art-world reckoning of sorts. In 2018, the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University presented “Posing Modernity: The Black Model From Manet and Matisse to Today,” which explored how the Black female form was essential to the development of modern art and the manner in which Black women were represented. The exhibition later traveled to the Musée d’Orsay.

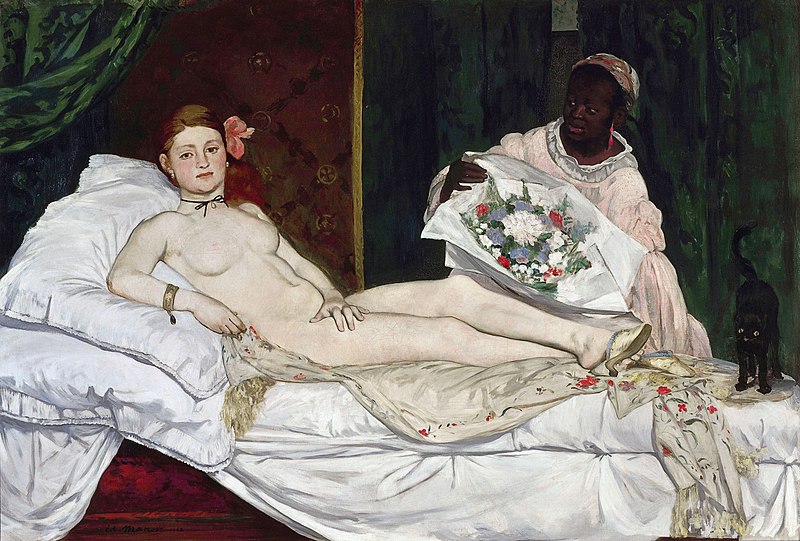

Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe

This article seems vague about Monet and Manet being different guys. Manet painted several pictures that included a black woman model, such as the famous Olympia. But I can’t find evidence that Monet ever painted a black woman.

“The Black model was always present but was omitted from the conversation,” Thomas says. “I think because of that [exhibition’s] exposure, because of that conversation around the Black model and looking back into history … we’re open to forging forth with some of these conversations that we’ve so long kind of circled around.”

Two revelatory exhibitions upend our understanding of Black models in art

In 2022, she created “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires avec Monet.” The mixed-media composition installed at l’Orangerie, along with three other collage paintings and photographs, as well as a video composition, depicts three women at rest in a landscape they have claimed as their own. Thomas created it in response to Monet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe,” which followed Édouard Manet’s painting of the same title.

Monet’s unfinished Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe

OK, now I get the chain of what passes for logic in contemporary art. You see, while Monet was primarily a landscape painter (he would occasionally have his wife and their child pose to add a focal point to the landscape—the story of M. and Mme. Monet is tragic and beautiful), which is boring to the black ladies writing and starring in this article, and so far as I can tell, though Monet never painted a black woman, Monet was inspired by Manet’s huge succès de scandale Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe of a naked lady at a picnic to begin painting his own less famous but prettier and more tasteful picnic picture. But he never finished it and instead went on to develop his famous style with fewer figures in his paintings.

So that gets us from boring old Monet, who is famous not for anything terribly controversial but because he painted a colossal number of beautiful paintings, to Manet, who was more of a 20th century–style operator with a nose for getting his paintings talked about.

Manet’s second most famous painting is another naked lady picture, Olympia, of a nude strumpet being presented with a bouquet of flowers, presumably from a gentleman admirer, by her black maid. To the black ladies involved with this article, it galls them that everybody looks at the white whore rather than at her black maid, who rather recedes into the dark background. It’s time for a Reckoning: from now on, everybody should look at lounging black women instead of lounging white women!

Manet’s second most famous painting is another naked lady picture, Olympia, of a nude strumpet being presented with a bouquet of flowers, presumably from a gentleman admirer, by her black maid. To the black ladies involved with this article, it galls them that everybody looks at the white whore rather than at her black maid, who rather recedes into the dark background. It’s time for a Reckoning: from now on, everybody should look at lounging black women instead of lounging white women!

Granted that’s pretty far from having much to do with Monet, but Monet/Manet, they were both white men.

Like her predecessors’, Thomas’s work is lush with flowers and trees. But instead of ivory-skinned picnickers and sunbathers, she positions Black women in their glory, with brown skin and Afros. They look back at the viewer. They aren’t staking a claim on a White world; they’re inhabiting their own realm, one in which Monet exists but over which they have authority. They’re at ease and self-satisfied.

In “Salle à Manger et Sofa avec Monet,” the dining room of Monet’s home is reimagined to incorporate parts of Thomas’s realm, including a pale yellow sofa that has served as something akin to a throne for the subjects of her portraiture.

Thomas’s aesthetic—not just the pieces at l’Orangerie, but her entire body of work—is a corrective. It’s a reclamation of history and future history.

“What I respond to and admire and visually love about Mickalene’s work is she doesn’t shy away from the 19th-century images because they’re fraught with all the layers and stereotypes of women of color,” says Denise Murrell, who curated the “Posing Modernity” show in New York. “She reimagines these images and gives us a sense of the subject and how these women would have, could have been seen by themselves or been seen by others.”

Murrell zeroes in on one of Thomas’s works from 2012, “Din, Une Trés Belle Négresse 1.” It features a Black woman dressed in a floral print and posed against a floral backdrop. She’s wearing a large shell necklace, and her hair is styled in a grand Afro that surrounds her face like a sacred halo. Her full lips are lacquered in a deep blackberry hue, and her eyes are dramatically highlighted in dark shadow. The title, translated, means Din, A Very Beautiful Black Woman, but Thomas uses the discomforting “négresse,” which in art history often has rendered individual Black women as an anonymous commodity.

“She’s taking all the physical features, the hair and lips, that have been stereotyped in a derogatory way in the 19th century and giving them full beauty and lushness. She’s not just presenting a 19th-century woman, but the woman of the current moment,” says Murrell, who is the Merryl H. and James S. Tisch curator at-large at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In Thomas’s portraits, “the attire is of the late 20th century, the pose, the affect, the stance. You could see them at parties or on the street. She’s making these arguments in the artistic language of the current moment,” Murrell adds. “They’re gorgeous and self-possessed. They’re the opposite of the pictorial subordination in previous depictions of Black women. They claim all aspects of their being.”

… One could easily imagine one of Thomas’s women reclining languidly in “Le Jardin d’Eau de Monet,” but they don’t have to be present for their ownership to be evident. It’s still clear that this landscape, this space, belongs to Thomas and her muses.