One Popperian way to test the validity of the popular hypothesis of White Privilege is to look at battles over who gets classified as white by the government.

A century ago, Middle Easterners successfully battled to get themselves declared white so they could share in White Privilege.

Today, however, the most politicized of the younger generation of Middle Easterners are adamant about shedding their White Disprivilege. From the Los Angeles Times:

Are Arabs and Iranians white? Census says yes, but many disagree

MARCH 28, 2019By SARAH PARVINI AND ELLIS SIMANI

Samira Damavandi knows that when she fills out her 2020 census form, she will be counted. But it pains her that, in some way, she will also be forgotten.

When asked to mark her race, Damavandi will encounter options for white, black, Asian, American Indian and Native Hawaiian — but nothing that she believes represents her family’s Iranian heritage. She will either have to choose white, or identify as “some other race.”

“It erases the community,” she said.

Roughly 3 million people of Southwest Asian, Middle Eastern or North African descent live in the United States, according to a Los Angeles Times analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. No county is home to more of these communities than Los Angeles, where more than 350,000 people can trace their roots to a region that stretches from Mauritania to the mountains of Afghanistan.

In past census surveys, more than 80% in this group have called themselves white, The Times analysis found. …

Arab and Iranian communities for years have lobbied the bureau to create a separate category for people of Middle Eastern or North African descent.

Over the last decade, it seemed the tide would turn — the Obama administration was considering proposals to ask questions about race and ethnicity in a different way, shifting not only how the government would count the Middle Eastern community, but the Latino population as well.

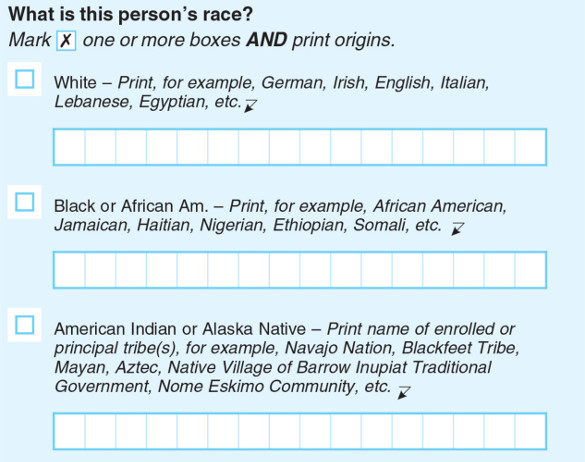

In 2018, however, the bureau announced that it would not include a “MENA” category. Instead, the next survey will ask participants who check “white” or “black” to write in their “origins” for the first time. Lebanese and Egyptian are among the suggestions under white.

The race question on the 2020 Census form.

For many, a write-in doesn’t go far enough because they identify as people of color. The bureau’s move was seen as a blow to a group already grappling with feelings of invisibility. Advocates say the category goes beyond issues of self-identity and has real-life implications for Arab and Middle Eastern communities, including the allocation of local resources.

“We are our own community,” said Rashad Al-Dabbagh, executive director of the Arab American Civic Council in Anaheim. “It’s as if we don’t count.”…

Those communities have struggled to become visible for decades, Karim said, especially in the post 9-11 period.

In 2015, the census bureau tested creating new categories — including MENA. Government research showed that Middle Eastern and North African people would check the MENA box if given the option. Without it, they would opt for white or “some other race.”

“The results of this research indicate that it is optimal to use a dedicated ‘Middle Eastern or North African’ response category,” a 2017 census report said.

The outgoing Obama Administration called for creating a MENA category, but the incoming Trump Administration then called it off.

… Sarah Shabbar grew up in Santa Barbara feeling underrepresented. In school, she was counted among the white students and wondered why she had to “conform to something I don’t agree with.”

“It was such a weird thing to grow up and be told, ‘You should be proud to be Jordanian. You should be proud of where you come from,’” said Shabbar, now a graduate student at Cal State Northridge. “None of these forms are allowing me to feel proud of it, because I’m just white according to them.”

After all, nobody could possibly be proud of being white.

Her parents would tell her to choose “white” if that’s how Middle Eastern people were classified by the government, she said. There wasn’t a discussion about identity, or what it would mean to properly classify the community.

“It’s like, khalas, just put it,” said Shabbar, using the Arabic word for “enough.” “For them it doesn’t matter. Until you apply for college … then it’s like, there’s no money for Arabs?” the 25-year-old said with a laugh.

It’s almost as if there is money for being nonwhite but no money for being white.

… Her parents, like many older Iranian Americans, saw it differently. She was raised in a home that believed Iranians were white, she said.

A Times analysis found that more than 80% of individuals of Southwest Asian, Middle Eastern or North African descent called themselves white in past census surveys. …

Experts say that generational divide is a common split within the Middle Eastern and North African community. For some, it stems from the notion of being from the Caucasus region — and therefore, literally Caucasian — and for others, identifying as white became a means of survival in a new country.

“Our parents came as immigrants and worked with this idea of aspirational whiteness, that if you work hard and put your head down you’ll be successful,” said Khaled Beydoun, who teaches law at the University of Arkansas. “But for young people, with 9/11 and now with Trump, whiteness means something specific.” …

Just as the Jussie Smollett hoax was due to Trump, according to Rahm Emanuel.

By the way, is Rahm Emanuel MENA? His father was born in Jerusalem in 1927. Jerusalem is in the Middle East, isn’t it?

Prior to the 2010 census, the Arab and Iranian communities in Southern California teamed up to spread a message: “Check it right, you ain’t white!” …

Some feel the census should follow the UC system’s example.

Nearly a decade ago, students successfully pushed for UC to add a Middle Eastern category on undergraduate admissions applications.

The University of California is banned by Proposition 209 from using racial categorization data, but for some unknown reason, they feel they must have it.

In 2013, the University of California became one of the first in the country to track data from students in a new category — “Southwest Asian/North African,” or SWANA — that included people of both Middle Eastern and North African descent. More than 10,000 freshmen applicants checked the box last year, nearly 5% of the total.

The University of California’s Southwestern Asian and North African group includes more countries than the census bureau’s Middle Eastern and North African category.

Students said they lobbied for the change on UC admissions applications because they felt “the Middle Eastern community has formed into an ‘invisible’ minority.” They settled on the term SWANA because they believed the term Middle Eastern was “problematic” due to its “colonial and Orientalist origins,” according to the resolution.

The category also expands on the census’ 2015 definition of who would be considered Middle Eastern by including Armenians and Afghans, among others.

For David Shams, the census question codifies a feeling he’s known all his life: a sense of straddling two worlds, both fully American and intensely proud of his Iranian heritage.

“It makes me feel unheard,” he said, “like I’m shouting into this void saying that we’re not white and no one is listening.”

The 36-year-old remembers a conversation he had with an administrator about the lack of inclusion of Middle Easterners in diversity scholarships when he was a student at Murray State University in Kentucky. The school official told him Iranians weren’t considered for diversity scholarships because they were white, and minorities needed help more than “you all do.” All the talk did was push “the misconception that we’re white,” Shams said.

“Having the federal government label us as white, while our social status is anything but, further stigmatizes our position in society,” said Shams. “We have no recourse. We have no way to talk about diversity or discrimination because if we’re white, we can’t be discriminated against based on race. And so we’re left in this gray area.”

The center of the Iranian-American community is Beverly Hills, California, so you can tell they are oppressed nonwhites who need diversity scholarships.