Republished by VDARE.com on September 25, 2003

The Times (London) November 8, 1986

NEW YORK–What do they know of English who only The Story of English know? Well, not that much, really. The companion volume to the television series being shown simultaneously in Britain and here in America is pretty simpleminded, albeit entertaining. But it does have one real, if inadvertent merit: it demonstrates how the past history of the New World can illuminate the present politics of the Old. In particular, it supplies the transatlantic dimension of a small nation whose virtues and very existence are fashionably ignored – the Protestants of Ulster, known to historians of American immigration as the 'Scotch-Irish. '

NEW YORK–What do they know of English who only The Story of English know? Well, not that much, really. The companion volume to the television series being shown simultaneously in Britain and here in America is pretty simpleminded, albeit entertaining. But it does have one real, if inadvertent merit: it demonstrates how the past history of the New World can illuminate the present politics of the Old. In particular, it supplies the transatlantic dimension of a small nation whose virtues and very existence are fashionably ignored – the Protestants of Ulster, known to historians of American immigration as the 'Scotch-Irish. '

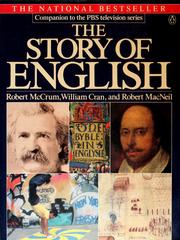

That The Story of English features the achievements of the Scotch-Irish so prominently is a comment on their magnitude. The book – by Robert McCrum, William Cran and Robert MacNeil – is in other respects a faithful reflection of the ultra-fashionable television mind. Its political liberalism renders it unwilling to contemplate the possibility that some regional and ethnic varieties of English may just be degenerations, rather than laudable expressions of linguistic anti-colonialism. It is so eager to emphasize the influence of black dialect on the English spoken by whites in the American South that it fails to mention the curious fact that, notwithstanding centuries of such influence, black and white Southerners can still instantly identify each other's race, because their accents remain quite distinct.

Some traces of this attitude affect the treatment of the Scotch-Irish. Their story begins, of course, with the 200,000 Scots sent to Ireland by James I in the early 17th century to settle confiscated rebel lands. The authors of The Story of English quip that 'when they landed in Ulster they fell on their knees and prayed to the Lord – and then they fell on the natives and preyed on them. ' They admit that the new settlers' industry transformed the province, formerly the most backward in Ireland. But, they say disdainfully, the settlers' were hard, mean and generally uncouth: 'they are said to have short arms and deep pockets. ' It may be doubted that any television type would care to apply such rude characterizations to the very similar group of settlers who created modern Israel.

Nevertheless, The Story of English is absolutely right to focus attention on the next act in the Scotch-Irish saga: the migration of some two million to the New World. This began after they had already developed into a unique cultural community, speaking an English that included archaic Scots and more recent Irish.

American settlement patterns are surprisingly stable. The Scotch-Irish still predominate in many areas of Pennsylvania, the hinterland of their great entry port of Philadelphia. 'At the time we were apprehensive from the Northern Indians,' wrote one colonial official. 'I therefore thought it prudent to plant a settlement of such men as those who had formerly so bravely defended Londonderry and Enniskillen as a frontier against any disturbance. ' The result in this case was the town of Donegal, near Pittsburgh. Later, echoing many subsequent British governments, the same official was having second thoughts: 'A settlement of five families from the North of Ireland gives me more trouble than fifty of any other people. '

However irritating this Scotch-Irish pugnaciousness, it was decisive in winning a continent for the English language. As Theodore Roosevelt wrote, the Scotch-Irish 'became the kernel of the distinctively and intensely American stock who were the pioneers of our people in their march westward. ' Pouring through the Cumberland Gap, the Scotch-Irish settled the whole Appalachian region. A later generation became the 'Mountain Men' who opened up the Rockies, and provided most of the troops who died at the Alamo with Davy Crockett, himself of Scotch-Irish descent, while wresting Texas from Mexico.

The legendary American frontiersmen with their long rifles and coonskin caps were Scotch-Irish. Their ballads formed the basis of modern Country & Western music. And their language profoundly affected American English, the most famous example, perhaps, being the use of the Irish 'cabin' to describe the log houses universal on the frontier. Today, according to The Story of English, an incredible 20 million Americans can claim Scotch-Irish ancestry.

In the Old World, the Scotch-Irish have sometimes recently seemed literally more royalist than the Queen. But in the New World, they formed the backbone of George Washington's army and provided at least five signatories of the Declaration of Independence.

Ironically, in contemporary Ulster, the Scotch-Irish community is in effect bound and gagged, deprived of any democratic ability to influence its future, clearly in mortal danger of being handed over to its hereditary Irish foe. It was an American president of Scotch-Irish descent, Woodrow Wilson, who introduced the world to the principle of self-determination. On the evidence of The Story of English, self-determination in this context would reveal that there are not one but two nations in Ireland.

The author is a senior editor of Forbes magazine in New York.

[Originally published in England, spelling and grammar vary slightly from American style.]