After a ruinous twenty-year war and countless deaths, the Taliban has taken back Afghanistan at lightning speed, as the US-trained army totally capitulated. The Taliban are back in charge, just as it was in 2001. Afghanistan has been a complete waste of American lives and resources. Even the Regime Media is shockingly outspoken in its condemnation of the Biden Administration’s chaotic capitulation [Media Turns Against Biden, But Tucker Isn’t Buying It: “Something Else Is Going On,” Gateway Pundit, August 21, 2021].

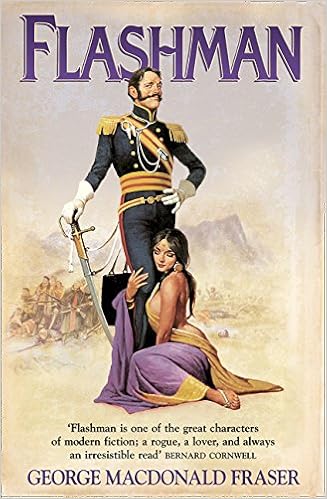

But America is far from the only country to have been humiliated by Afghanistan. It is known as the “Graveyard of Empires” for a good reason: The British, the empire before us, were forced into a devastating retreat from Afghanistan in 1842. (Steve Sailer pointed out in 2019 that the 1842 debacle was the subject of George MacDonald Fraser’s first Flashman book.) They simply could not tame the place, as they could India and so many other countries that were part of their empire. Why is Afghanistan so difficult to colonize? Why does it seem to be in a state of perpetual war?

But America is far from the only country to have been humiliated by Afghanistan. It is known as the “Graveyard of Empires” for a good reason: The British, the empire before us, were forced into a devastating retreat from Afghanistan in 1842. (Steve Sailer pointed out in 2019 that the 1842 debacle was the subject of George MacDonald Fraser’s first Flashman book.) They simply could not tame the place, as they could India and so many other countries that were part of their empire. Why is Afghanistan so difficult to colonize? Why does it seem to be in a state of perpetual war?

One key problem: Afghanistan’s high level of ethnic diversity. Contrary to advertisement, Diversity is not Strength. In his 2012 book Ethnic Conflicts, Finnish political scientist Tatu Vanhanen found that there was 0.66 correlation between ethnic diversity and ethnic conflict and that ethnically diverse states are almost always politically unstable and riven by war

Afghanistan is named “Afghanistan” after its largest ethnic group, the Afghans, also known as the “Pashtun,” who are Caucasian. However, the Pashtun only comprise about 42% of the population. There are Turkic groups like the Tajiks, who live in the north, feel affinity to neighboring Tajikistan and make up about 27%, and the Uzbeks, who look to Uzbekistan and make up 4%. Then there are the East Asian-derived Hazara (9%); and many other smaller groups [Afghanistan, World Population Review, 2021].

love Gorgeous Hazara girls and Hazara traditional dress#hazards pic.twitter.com/TdJ1IrSIDZ

— jalila gulistani (@Jalila75293495) August 30, 2016

The majority of the population, therefore, don’t have a strong sense of being “Afghan.” They tend to put their ethnic interests first. This means that there is always going to be ethnic conflict, especially in a poor country where people struggle to survive. There was serious conflict within the Mujahidin, which fought the 1979 Soviet invasion, between the Tajiks, who took over after the Soviets withdrew, and the opposition Taliban, who were (and are) Pashtun [Pashtuns, Minority Rights, 2021].

Worse still, the Hazara, the original population of Afghanistan, are a repressed minority who have every reason to hate the now-dominant Pashtuns. Until the early nineteenth century—when the Pashtuns started expanding from their base in Kabul—the Hazara made up as much as two-thirds of the population of Afghanistan. In the 1880s, the Afghan emir declared jihad on the Hazara, because the Pashtun were Sunni Muslim and the Hazara were mostly Shia Muslims and thus “infidels.” In 1893, the Pashtuns massacred an astonishing 60% of the Hazara. Others were driven off their lands and sold into slavery. As recently as the 1970s, Pashtun children were taught that killing Hazaras was a shortcut to paradise. Hazara now have the worst jobs and are routinely discriminated against. When the (Pashtun) Taliban came to power in 1996, they declared a new jihad on the Hazara. Subsequently, the Hazara played a significant part in the post-Taliban government [Hazara, Minority Rights, 2021].

And as if these ethnic divisions were not enough, the Pashtun themselves are very far from united. Tajiks identify as Tajiks and Hazara identify as Hazara. Pashtuns, by contrast, identify with their tribe or their clan within their tribe, possibly because the mountainous nature of Afghanistan had made people insular, cut off from other people for lengthy periods and, so, highly psychologically and genetically separate from them. So you get groups of families in a hierarchy, some of whom look down on and oppress other groups of families, due to having a different common ancestor [Pashtuns, Minority Rights, 2021]. There are about 60 Pashtun tribes and about 400 clans, all with various degrees of enmity towards each other.

President Hamid Karzai, although himself a Pashtun aristocrat, effectively allied with the Uzbeks, Tajiks and Hazara in order to stay in power under a democratic system. The result, it seems, was electoral malpractice whereby Pashtuns were prevented from properly campaigning, such as in the 2010 parliamentary elections [Pashtun Candidates Protest in Herat, Institute for War and Peace Reporting, December 16, 2010].

In other words, the Pashtuns dominated the country under the Taliban, were marginalized by opportunistic members of their own group in alliance with minorities under the Americans (sound familiar?!), and now, under Taliban, are in charge once again.

Popular support for the American presence in Afghanistan was, unsurprisingly, “very low” among the Pashtun, while support for the Taliban is high [The Taliban’s Winning Strategy, by Gilles Dorronsoro, 2009]. And not only was the American-backed Afghan army not being paid properly—leaving them open to Taliban offers—but they tended to be of very low caliber (many were drug-addicts, giving them a financial incentive to collaborate with a foreign-backed regime, but flee when “the going gets tough”) and, in many cases, literally ex-Taliban, such is the popular support for the Taliban among Pashtuns [Observations on Afghanistan, by Noah Carl, Noah’s Newsletter, August 18, 2021]. No wonder they didn’t put up much of a fight.

To add to the chaos, it seems likely that average Afghan IQ is very low. Video clips posted by Jared Taylor show U.S. advisors straightforwardly dismissive of their trainees’ abilities. According to Richard Lynn and David Becker's book The Intelligence of Nations, there are no reliable Afghan IQ studies. However, the IQ of neighbouring Pakistan—with which there is significant ethnic overlap, Pashtuns make 15%-18% of the population—is 80. Psychologist James Thompson, organizer of the London Conference On Intelligence, says the highest estimate he has been able to find for Afghanistan is 83 [Afghan Intelligence, Unz.com, August 16, 2021]. He points that this is too low to use, and especially to service, American-style weapons. Afghanistan also has a high first or second cousin marriage rate of 42%, which is likely to suppress its IQ [Consanguineous marriages in Afghanistan, by K. Saify & M. Saadat, Journal of Biosocial Science, 2011]. Similarly, in Pakistan, the consanguineous marriage rate is 50% [Keeping it in the family: consanguineous marriage and genetic disorders, from Islamabad to Bradford, by M. Merten, BMJ, April 2019].

Afghan refugees are notoriously badly behaved [I've Worked with Refugees for Decades. Europe's Afghan Crime Wave Is Mind-Boggling, by Cheryl Benard, National Interest, July 11, 2017].Their aggressiveness might be explained by hereditary personality traits that go beyond IQ, as J. Philippe Rushton argued is the case with blacks [Personality and genetic similarity theory, Journal of Social and Biological Structures, January 1985]. Their ecology has produced high levels of tribalism and clannishness and thus hostility and disdain towards those who are not part of the tiny in-group.

Almost every Afghan head of state since the eighteenth century has either been assassinated or deposed, with the prominent exception of Hamid Karzai, who was installed by the American government. The last King of Afghanistan (Mohammed Zahir Shah) did manage to reign for 40 years before being deposed in 1973. But even his period of relative peace was marked by rebellions by small mountain tribes as well as by the Hazara.

It is the geography of Afghanistan that helps to cause these divisions and make the place ungovernable. The mountainous nature of the country means that rebels can always retreat into, and hide behind, natural fortresses, regroup and rebel anew.

This is already happening. The elected Afghan president, a Pashtun called Ashraf Ghani, has resigned and fled the country [Ghani denies taking large sums of money as he fled Afghanistan, Al Jazeera, August 18, 2021]. However, his vice-president, a Tajik called Amrullah Saleh, has declared himself president. The Taliban may control most of the country, including the capital, but Saleh, and part of the national army, still control the region of Panjshir, which is north of Kabul and surrounded by mountains [Afghan envoy says hold-out Panjshir province can resist Taliban rule, Reuters, August 18, 2021].

This region is Tajik, as is Saleh. So, in effect, a Tajik region of Afghanistan is holding out as independent from what is now a Talban-dominated (and thus Pashtun-dominated) state [Resistance fighters drive Taliban from 3 districts in the mountains north of Kabul, by Matthew Rosenberg, NYT, August 21, 2021]

Ethnic divisions, tribal divisions, clan divisions and fortress-like mountain ranges to retreat into…This is why Afghanistan is rarely at peace and is hard to control.

And it is why the U.S. should never have tried to “nation-build” there—even if it were not crippled by Politically Correct Woke Delusions.

Lance Welton [email him] is the pen name of a freelance journalist living in New York.