Earlier Erin Aubry Kaplan content: Black Woman Gets Angry At A Becky, Blames It On Trump and NYT: "I'm a Woman of Color, So Let's All Talk About Me!"

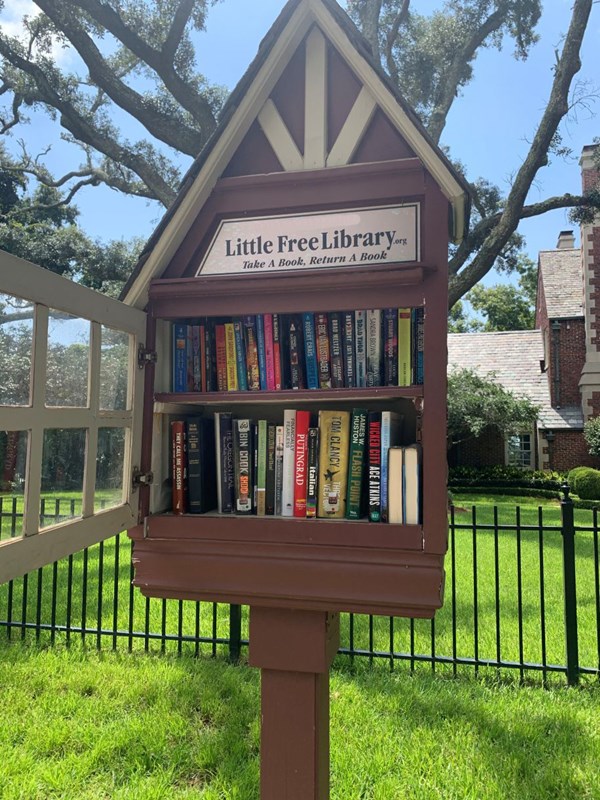

These days, lots of people own more books than they have room for in their houses. So, in upper middle class white neighborhoods, some have taken to erecting a birdhouse-like “little free library” on their front lawns next to the sidewalk to invite passersby to grab a few unwanted books. It’s all rather twee, but it’s so genteel it likely boosts property values a little.

These days, lots of people own more books than they have room for in their houses. So, in upper middle class white neighborhoods, some have taken to erecting a birdhouse-like “little free library” on their front lawns next to the sidewalk to invite passersby to grab a few unwanted books. It’s all rather twee, but it’s so genteel it likely boosts property values a little.

From the New York Times opinion page:

Is My Little Library Contributing to the Gentrification of My Black Neighborhood?

Dec. 5, 2021, 11:00 a.m. ETBy Erin Aubry Kaplan

Ms. Aubry Kaplan is a journalist and author who grew up in the South Central section of Los Angeles and nearby Inglewood.

About a year ago, I decided to build a library on my front lawn. By library, I mean one of those little free-standing library boxes that dot lawns in bedroom communities around the country — charming, birdhouse-like structures filled with books that invite neighbors and passers-by to take a book, or donate a book, or both.

I’d spotted the phenomenon on walks through upscale, largely white neighborhoods around Los Angeles and immediately resolved to bring it home to Inglewood. Why not? A library is not so much a marker of wealth and whiteness as it is an affirmation of community and cozy, small-town camaraderie that Inglewood, a mostly Black and Latino city in southwestern Los Angeles County, has plenty of. We deserved no less.

Prepandemic, Inglewood was gentrifying

Inglewood has a very mild year-round climate, it's only a few miles from the beach, and its freeway is close to countless jobs.

But it's under the inbound flight path of jets landing at Los Angeles International Airport. It was a virtually all-white municipality at the beginning of the Jet Age in 1960, when the new jetliners were very noisy and few homes had central air-conditioning or double-paned windows.

Soon Inglewood became mostly black. Much of the LAX workforce, as at many airports, is black. I think this black preference for transportation service jobs goes back to 19th century Pullman porters, but I’ve never seen it discussed. And by 2010 the town was majority Latino.

Under the flight path has been a good place for sports complexes like the old Hollywood Park racetrack, the Forum basketball and hockey venue, and the lavish new SoFi football stadium for the LA Rams (where next February’s Super Bowl will be held).

But jets are quieter these days and soundproofing is better, plus North Inglewood is not quite under the flight path. So ever since the announcement of SoFi Stadium a half dozen years ago, there has been growing interest in buying homes in Inglewood among frequent fliers who can’t afford other LAX-convenient places like Manhattan Beach.

, another reason I’d been inspired to do the library: I wanted to signal to my longtime neighbors that we had our own ideas about improvement, and could carry them out in our own way. …

Then one morning, glancing out my front window, I saw a young white couple stopped at the library. Instantly, I was flooded with emotions — astonishment, and then resentment, and then astonishment at my resentment. It all converged into a silent scream in my head of, Get off my lawn! …

Now that they were in front of my house, curious about this new neighborhood attraction, I didn’t know how to feel. By bringing this modern cultural artifact here from white neighborhoods, had I set myself up, set up the neighborhood? Was I contributing to gentrification and sending the wrong message about how I wanted the neighborhood to be?

What I resented was not this specific couple. It was their whiteness

She’s not anti-white, you see, she’s anti-whiteness, which is totally different for reasons.

, and my feelings of helplessness at not knowing how to maintain the integrity of a Black space that I had created. I was seeing up close how fragile that space can be, how its meaning can be changed in my mind, even by people who have no conscious intention to change it. That library was on my lawn, but for that moment it became theirs. I built it and drove it into the ground because I love books and always have. But I suddenly felt that I could not own even this, something that was clearly and intimately mine.

As the couple wandered on, no books in hand, I thought about how fragile my feeling of being settled is. It didn’t matter that I own my house, as many of my neighbors do. Generations of racism, Jim Crow, disinvestment and redlining have meant that we don’t really control our own spaces. In that moment, I had been overwhelmed by a kind of fear, one that’s connected to the historical reality of Black people being run off the land they lived on, expelled by force, high prices or some whim of white people.

On the other hand, as we all know, no whites have ever been run off the land they lived on by violent crime.

One of the most famous examples of that displacement happened several miles south of Inglewood. Bruce’s Beach, a Black-owned resort, once thrived along the coast of tony Manhattan Beach, until it was seized by eminent domain in 1924 by white city officials. They claimed they needed the land for a public park, but they didn’t build one for more than three decades. It’s clear they simply wanted the bustling holiday and leisure spot and the Black people it attracted gone. That parcel was recently returned to the descendants of Willa and Charles Bruce, who owned it — an extraordinary example of reparation, but an isolated one that still leaves the problem of Black unsettledness intact.

… It has to be said that there’s nothing inherently wrong with the Black-, Latino- and immigrant-rich neighborhoods that resulted from those flights. Community has always been our greatest asset, and its greatest source of capital. But now, as younger generations of white people move back to the neighborhoods their parents shunned, in the phenomenon I call “white return,” it all suddenly feels up for grabs — again.

All she wants is to live in an all-black neighborhood with low crime, high property values, and Little Free Libraries on everybody's block. If she can’t have that, the white man must pay.

Instead of the blatant racism of what happened at Bruce’s Beach, we now have gentrification. It’s perfectly legal, but ultimately it causes the same racial displacement, on a much larger scale. The stratospheric rise in home prices alone has meant that the Black population of Los Angeles has been declining for decades, and has dropped to around 9 percent.

… Ultimately, the moment with the couple I saw through my window raised for me a serious moral question about how I should act. Screaming at them to get off my lawn would be adopting the values of the oppressor, as my racial-justice activist father used to say. Yet my resentment was not analogous to the white resentment of generations past (and of now, I’d argue). White resentment has always been legitimized, and reinforced, by legal and cultural dominance, a dynamic evident in everything from the rise of Trumpism to the current battle against the political boogeyman of critical race theory.

After all, the New York Times is constantly printing op-eds by white people recounting how they were forced to flee from their ancestral neighborhoods by black violent crime, while the Washington Post ran seven articles about different angles on the massively publicized news that blacks comprised 56.5% of known murder offenders in the 2020 crime stats.

My little library, affirming as it is, is also an illusion; it can’t save our neighborhood. Still, in 2021, it has become increasingly important to maintain and grow Black space, on its own terms. As I watched the white couple peruse my little library, the most complicated feeling of all was the brief, bittersweet satisfaction I took in watching them drawn to my lawn, and to my idea. It felt empowering and hopeful on the one hand, defeating on the other.

So what message do I hope they took from my library? The same message I wanted to send to the rest of my neighbors, my community: Black presence has value — in every sense of the word, and on its own terms.

That value should make the casual displacement of Black people untenable, even immoral. And that will take much more than a little library to rectify.